There are a number of terms for the game depending on when and where you look. The game is called Nard, or some version thereof (narde, nardi, and etc...), in Persian or Frangieh (which apparently means Frankish/French) in Arabic. There are also variations of the game which are mentioned after the 16th Century. I will mention that Mabouseh (mahbusa) is a game popular from the 17th Century to the current day in the Middle East and is played exactly as a game described in Alfonso X's book of games from the 13th Century. It's likely that game was played in the Middle East prior to the 16th Century but I can't confirm that.

Neither can I absolutely confirm that a game almost identical to modern backgammon was played. BUT, the evidence strongly supports the assertion that it was. Let me lay this out for you. Language is tricky and I cannot offer any written evidence that the tables game reference in the writings above is modern backgammon. I have, therefore, relied upon visual sources. There are three images in particular.

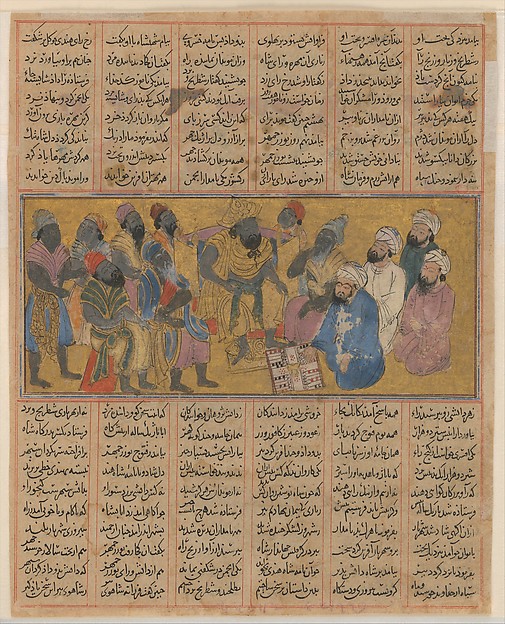

Image 1

Image 1 is a very early 14th Century image held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. You can see it here. This is a relation of the origin myth of backgammon showing the diplomat/adviser Burzoe instructing the King of India in the game. The game pieces are red and black on a white board (which is interesting in and of itself) and the pieces are distributed in a fashion that very strongly resembles the starting distribution of pieces in modern backgammon.

Image 2

Image 2 is a close up of a 15th Century illumination in the Anthology of Baysunghur in the Berenson Collection in the Villa I Tatti. Here we see princes playing at tables and, again, the distribution of the pieces very strongly resembles the starting distribution of pieces in modern backgammon.

Image 3

Finally we have Image 3 which is a 16th Century Turkish illumination depicting Burzoe demonstrating chess to King Khusraw. This piece is held by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Note, again, the distribution of pieces.

The distribution of pieces is important because it is unique amongst the games that we know about and we have a fairly extensive knowledge of tables games from European sources. This distribution is highly unlikely, but not impossible, to occur playing any of the other variations of tables games. On this basis I feel confident that someone at an SCA event playing modern backgammon, leaving out the doubling cube and the doubles rule, would not be far wrong at all.

Before I end this I'd like to point out a couple of other things I find interesting. Some of you will have noted the distinctive shape of the boards which visually distinguishes them from European style boards. You may also have noted the cups in the center of the boards in Image 1 and 2. I speculate that this cup was used for the dice and they were either cast into it or kept in the cup and the entire cup shaken and then set down. And last, since all the scenes depict the rich and powerful the boards are, accordingly, quite large. I have no idea what boards for the less wealthy might have looked like. These images don't provide us with any evidence for the number of dice that would be used in play. I suspect two dice were used based on the listing of backgammon equipment provided by the 10th Century writer Mas'udi, but I cannot be certain of this number of the basis of this sparse evidence.

I also want to remind you that I have the rules for many tables games and, more importantly, the sources they are derived from in a PDF booklet here. You can find a set of rules for Todas Tablas, which is the game I believe we are seeing, in this booklet.

_LACMA_M.73.5.586.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment